Sequential stretching is primarily my own invention, but it builds on the work of many other somatic bodywork techniques. I didn’t set out to make a new stretching technique; It happened because the existing techniques were not working for me. It was born of my own experience with losing flexibility early in life, finding an activity I love that needs flexibility later in life, and finding an effective way to get flexible through experimentation.

Similar Origins

In several ways, the origins of the sequential stretching techniques are similar to the origins of the Alexander Technique, which was created after its founder, Frederick Matthias Alexander, suffered from voice loss when reciting Shakespeare. Alexander developed his technique to fix his own voice problem and then taught it to help many others. Sequential stretching was birthed while attempting to solve my own voice problems with singing.

Beginnings of My Flexibility Problems

I’ve had flexibility issues for most of my life, although it wasn’t always clear to me that flexibility was the problem. I first started noticing that I wasn’t very flexible in my early teens. For much of elementary school, my physical education classes used a sit-and-reach box to measure flexibility for the Presidential Physical Fitness Test once each year. This is a simple device that measures how far you can bend forward when you sit down and reach toward your toes without bending your knees. I passed the flexibility portion in the early years, but when I was around 10 years old, I just couldn’t reach the passing mark any longer. This also corresponded with a growth spurt, so my friends and family told me that it was just because my legs were longer, so my toes were too far away to reach now. I mostly accepted this explanation because it seemed like, even though I stretched almost daily, I never seemed to get any closer to touching my toes with straight knees. I was also told that some people are just naturally more flexible than others and that I was just one of the less naturally flexible ones.

I also noticed that around this time, despite being skinny and physically active, most of my fellow classmates surpassed me in athletic ability. I did pretty well in some activities, like running, push-ups, and sit-ups, that mostly depend on cardiovascular ability or strength, but I did poorly in sports like baseball, basketball, soccer, and tennis that require more finely coordinated body movements. In high school, I discovered I really liked computers and programming, so I decided that athletics was just not my thing. I made sure to keep up my fitness with some sort of exercise for health, but I mostly gave up on getting good at athletics.

I did put in a solid effort to get good at tennis, eventually taking several college classes in it. I got to the point where I could defeat beginners and hold my own in a match with beginner-intermediate level tennis players, but hit a plateau where I was not really improving much despite years of practice. I remember one of my tennis teachers commenting on how I lacked the smooth strokes that could produce the whip-like motion needed for a good tennis stroke.

Inflexibility Turned Painful

At age 16, I started having painful upper back/neck/shoulder spasms that would last for several days, then get better on their own. This was around the time that I discovered a love of computer programming on early Apple Macintosh computers. I would spend long hours at the computer using the mouse extensively, as the mouse was often the only input option for many tasks on the Macintosh in the early nineties.

These spasms got worse at age 24 after I started working at Intel. I finally learned all about ergonomics and how my posture at the computer, and particularly the mouse usage, was probably causing these spasms. The company nurse identified the neck and trapezius as my main problem muscles and gave me some exercises to stretch those out. I would do those as directed, but only when I was having painful episodes at first. These problems slowly escalated until around age 40, I started doing them several times a day to try to prevent these episodes. This seemed to reduce the occurrence of the neck/shoulder spasms, but they still came back now and then. Sometimes they would become so severe that I couldn’t bend my neck or turn my head even slightly without pain. The episodes would usually come after some minor action that felt briefly painful like a quick head move in the shower or a tennis stroke that hurt a little.

I also saw several doctors, physical therapists, and chiropractors about these spasms. Their treatments were all pretty similar and all of them gave me a handout with the same basic back/neck/shoulder stretches to perform. Often the pain went away within a week, so I usually didn’t return for many follow-up appointments. One time, when I did a follow up appointment after feeling better, the chiropractor commented that my shoulders felt “hard as a rock” before asking how I felt. When I informed her that my pain was all gone, she looked puzzled, clearly expecting that I would still be in pain based on how tight I felt to her. This incident made it clear to me that these muscles were not in a healthy state even when they felt pain-free.

Learning to Sing

In my late 30’s, after going through much of life as a non-singer, I discovered I really enjoyed singing. I wanted to get good at it and perhaps even try to make a career out of it, so I signed up for a classical voice class at American River College near Sacramento, CA. Even though I was not someone who was comfortable performing in front of people, I enjoyed the class immensely and ended up taking the entire four-semester voice series in the evenings while working as a computer engineer at Intel.

These classes helped correct many problems with my singing technique, like how to sing from the body, how to relax tension, and how to keep the vocal passageways open while singing. This was also my first introduction to the Alexander Technique, another somatic bodywork technique. My teacher for the last three classes, Catherine Fagiolo, had studied Alexander Technique and used it occasionally during voice class. During one lesson, she had me try several different singing exercises, like singing with my nose plugged, to see if I could feel small differences in how my body felt when I sang with those techniques. When I told her it didn’t feel any different, she noted that feeling such small sensations in my body seemed to be especially difficult for me. She suggested that I practice listening closely to my body for a day. It sounded like new-age hokum to me at the time, but now I see she had identified a major lack of mindfulness of my body sensations that was preventing me from obtaining a flexible body.

Later voice lessons would identify some key body movements that I was unable to properly execute before singing. I would hear commands like: “Open your throat,” “Open your neck,” and “Open your chest,” and would diligently attempt to perform these actions. I had also heard more figurative techniques with a similar goal like feeling my body get wide like a tree trunk. I had some idea of how to do these things, but my body would always fight back with tightness against opening up, leaving me unsure if I was doing these body movements wrong.

I worked hard in the class to understand everything needed to be a good singer and had wonderful instructors to guide me. I practiced frequently both the songs we learned as well as vocal technique. Despite being nervous every time I got up to sing for the class, I volunteered frequently to do so in order to get as much feedback for improvement as possible. I also read everything I could get my hands on about improving my singing voice and practiced those techniques regularly. However, at the end of the class series, I didn’t have anything close to the open, operatic tone that a classical singer strives for. This might have ended up a huge disappointment, but in the final few weeks of the last voice class in the series, I had an epiphany that began my journey to a better singing voice by getting more flexible.

Early Discoveries

When the first epiphany happened, I was playing around with the different muscles of my mouth and throat to try to get a more open throat and lifted soft palate, both of which are important for good singing technique. I had been a regular cannabis user for a couple of years and was high at the time. At one point, I tried a combination of opening my throat and lifting my soft palate with rotating my head similar to a face-clock exercise I had been taught while struggling with spasms.

After doing a couple of circles with my head and trying to open my throat, I felt a pop in my throat, unlike anything I had experienced. It felt like my throat had just opened for the first time in my life. I got excited immediately with the discovery, thinking that I had just solved a major issue with my singing voice. I tried several more rotations of my new exercise and got a few more satisfying pops from my throat. It didn’t feel like I was just popping something out of place and back again. It felt like each pop was freeing up additional muscles in my throat.

At this point, I had just one more performance left in the voice class series before it was over and a couple of days left to prepare for it. I set my mind to doing this new stretch as many times as it took to free up all the muscles in my throat before the final performance. I thought I would shock everyone with my newly found vocal resonance as the perfect show of mastery to cap the end of the class series. I practiced this new stretch day and night to prepare for the last performance. On the night just before the performance, I found that the pops in my throat while doing this stretch seemed to stop, so I thought I had completed releasing my throat muscles.

On the night of the performance, I started to feel that some of the muscles that were releasing were slipping back into a tight state that I could pop open again with my new stretch. It didn’t feel like the same sections of muscle were reverting to their prior state; It felt more like other sections of muscle were moving up into the throat, replacing the ones I released with other tight sections of muscles from down deeper. The feedback from friends after the performance was that I sounded about the same as before. I was crushed but determined that I had made some great discovery with my throat stretch anyway. It felt like I just had to work through all the layers of tight muscle before I would finally have the freedom to fully open my throat.

Alexander Leads the Way

Professor Fagiolo gave several mini-lessons on the Alexander Technique during the voice classes that would lead to additional epiphanies for me. These taught how humans unconsciously add unnecessary tension to everyday movements. By becoming aware of this tension, we can naturally stop doing it. Slowing down these movements makes it easier to sense tense parts of common motions. The main movements I focused on were: walking, sitting down, and standing up from a seated position. I tried performing each of these as slowly as I could to see if I could sense areas where I was unconsciously tensing up.

The first time I tried slow-motion walking, I almost immediately felt muscles in my back and legs tightening up. Just as quickly, I stopped tensing them up without even really thinking about it. As I took a few more steps, I felt and heard muscles throughout my body begin to pop and crack in pleasant ways. Eventually, my walking movement seemed to get gentler and more graceful.

I had similar epiphanies while practicing slowly sitting and standing up without tensing up. I realized was tensing up and then falling into seats instead of gracefully sitting down. When standing from a seated position, I found that I was tensing up my body, then pushing up my body with my arms and legs. Alexander teaches that when sitting, you should be able to change your mind at any point in the motion and go back to standing. That would be impossible the way I was sitting. I had been sitting and standing in this poor manner for so long that the muscles that would balance me and hold me up by my legs had become too weak to be able to sit or stand correctly. Two stretch sequences I do on a regular basis involve performing these motions in slow motion.

My early success with ridding my body of this unnecessary tension made me want to find every way that I was adding tension to my body and put a stop to them. I also found that there is a ripple effect where releasing tension in one part of my body made me more aware of tension in other parts of my body, allowing me to release even more tension. This was greatly enhanced when I used cannabis, as it not only put me in a more relaxed state, but also amplified the light sensations coming from my body as I released tension.

As my walking became less tight and I became more mindful of my body, I started to believe that I might be constantly holding up my shoulders. I had read about people holding up their shoulders constantly and how it could cause a lot of physical problems. I tried pushing my shoulders down, but they seemed to want to pop back up. I kept at it, trying to gently pull them down just until I felt some slight resistance while I was standing, walking, or sitting at a computer. It felt very strange and unnatural to keep my shoulders down at first. I began to doubt that I was doing anything wrong until after a few days of determined efforts to keep my shoulders low, I started feeling satisfying pops and clicks in my shoulders like what happened when slow-motion walking. My shoulders eventually settled on their new lower resting position, likely improving my posture, as well as freeing up some long overworked muscles.

Expanding to Hip Stretches

I knew that flexibility was important to singers from the voice classes and from reading how muscle tension down as low as the knees could affect singing ability. Considering how the head/neck rotation while holding open my throat seemed to be helping my flexibility in my neck and throat, it seemed that the key to an effective stretch was that adjacent muscles to the muscle being stretched needed to be in motion. I set out to see if this theory could help other areas of poor flexibility in my body. After reading articles on flexibility and specifically being unable to touch your toes, I decided that my inability to touch my toes with straight knees was likely the result of poor hip flexibility.

My early attempts to find effective hip stretches with adjacent muscles in motion didn’t feel like they were working, though. Every hip stretching position I tried resulted in the hips and all the adjacent muscle groups being very tight even in the initial position. I couldn’t add any motion to them because I was so tight when beginning the stretch that hardly any adjacent muscles would move.

I did find one hip/lower back stretch position where I had some freedom of movement in adjacent muscles in the stretch. I adapted the knee to chest stretch where you lie on your back and bring one knee to your chest using your arms to bring the knee close to your chest. From that position, my modification was to use my hands to guide the bent leg in a semicircular path that opens the hip outward while straightening the knee. I would use the arms to hold the leg in place for most of the movement so that little or no engagement of the hip and lower back was needed. On almost every iteration of the movement, I would feel a big pop of my hip as my leg straightened. Similar to the throat pops during my throat stretch, this felt like I was making progress by releasing different muscle fibers on each iteration. I also found that this seemed to work better on my left hip than my right hip. The key findings of this experiment seemed to be that in order to get a good stretch:

- The muscle being stretched needs to be disengaged.

- The muscle being stretched and adjacent muscles need to start from a position of relaxation.

- Using non-involved muscles (hands and arms) to perform the motion helps to keep the involved muscles (hips and lower back) relaxed. This would be the basis for the Muscle Isolation concept in sequential stretching.

- The slower the motion, the deeper the stretch.

A Third Effective Strech

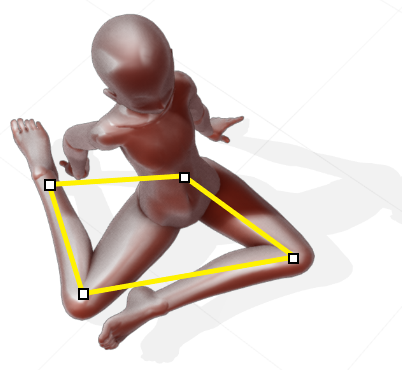

The next effective stretch I found came from a sitting position that my girlfriend showed me called deer pose:

With virtually every other sitting position I tried, including cross-legged, hurdler’s stretch, and the hero pose from yoga, my hips felt too tight and could not be relaxed. With this left deer pose, I could use my hands to keep my balance while my hips relax. This gave me the freedom to add the adjacent muscle motion that seemed to be needed in order to release tension in my body. This evolved into the Walking Tripod stretch sequence. With this sequence, I found that in order to get a good stretch:

- Focussing my attention on a desired body position or direction of motion instead of focusing on the muscles being stretched allowed my body to determine which muscles are ready to release. I named this concept Simplified Positional Posing and Movement (SPPM).

- The squeaky wheel gets the grease. You don’t have to stretch equally on both sides. Sometimes one side has fewer blocks to effective stretching at a given point in time. Keep trying stretching on both sides for brief periods, but focus the most time on the positions that are ready to release.

- Taking pauses to relax at different points along the motion helps keep tension from building up.

Naming the Beast

I found that calling these exercises stretches didn’t really sound right, as they didn’t follow the basic pattern of any static stretches that I had learned: move to a position of tension, hold for 30-120 seconds, and release. The key to their effectiveness seemed to be the addition of motion to a static stretch, so I thought I might call them dynamic stretches. I found that name was already taken by another type of stretching that was not really that similar to what I had found.

The way I would pause to relax at different points along the motion reminded me of a sequence of static stretches, with each pause being a brief static stretch that I named a microstretch. These microstretches would last between 1 and 30 seconds each and would be more frequent as the tension level of the stretch increased. I found that they were more effective when I told myself that I needed to hold that microstretch comfortably for five minutes or more, as that triggered my body to perform some shifts in posture for better balance and relaxation. Hence, the name sequential stretching was born.

Beginning My Body Transformation

By this point, I knew I was tight in my hips and my neck/throat muscles. As I learned new stretches through experimentation and modifying existing stretches from yoga, I found that those were only the beginning of my flexibility issues. Learning to stretch my neck taught me that adjacent muscles in my jaw and lower back were tight. Learning to stretch my hips taught me that my lower back and knees were tight. Learning to stretch those taught me that my everything was tight.

As I practiced my neck/throat stretch, I would sometimes just close my eyes, focus on the sensations coming from my muscles, and try to determine the optimal path to take with my head so that I maximized these strange sensations. When I would get to a part of the circle where my muscles felt very tight, so I would try to steer the path of my head to a position that felt looser. If I didn’t go wide enough on the circle, I wouldn’t feel any tightness and it didn’t feel like it was doing anything. A picture would form in my mind of a circle-like shape with different colors representing different levels of tightness along the path.

Using the technique I later named tension visualization, I would try to remember how each point on the circle felt the last time I passed by and see if that changed on the next rotation. Although my head and neck were moving in a circular direction, I would often feel and visualize movement inward toward the center of the circle or outward away from the circle. These would begin to form a picture in my head of being inside a cavern where different iterations of the circle formed the walls. As I pictured how this cavern evolved during the stretch, it felt like the cavern was slowly expanding. This eventually became the Expanding Cavern stretch sequence.

Long Hours Stretching

I now had three effective stretches to work on my two main areas where I had identified tightness: my hips and neck/throat. I would perform these stretches for hours on end, despite having heard recommendations from dozens of experts that no more than a couple of minutes per stretch was needed. I could feel that the longer I did these stretching sequences, the more new places in my muscles I reached that were not getting stretched earlier in the sequence. I would use the lessons I learned developing these initial three stretches to cover stretches for nearly the entire body. All of these required hours of practice to reach what felt like optimal effectiveness, so I knew I needed a lot of free time to devote to these if I really wanted to get all the benefits.

I enjoyed the physical sensations and mental relaxation of doing these stretch sequences tremendously. I also started to believe they were the key to improving not just my general flexibility, but also my athletic pursuits in singing, tennis, and weightlifting. I also noticed that my recurring neck and shoulder pains were happening less and would even go away faster when I practiced my techniques around the painful areas. Practicing these stretching techniques replaced or complemented virtually all of my leisure activities.

At age 42, I had saved up so that I could retire from computers and become a full-time musician of some sort. I still wasn’t a great singer, but now I had tons of free time to practice and become a great musician. I felt like being a musician would be a fun use of early retirement, but I quickly felt a much stronger pull to make this stretching technique the main part of my post-retirement career. Since I had retired that year, I now had my days free to practice these techniques as long as I wanted.

Finding My True Calling

The techniques I had developed, while more complicated than anything else I had read on stretching techniques, seemed rather simple and felt so effective. I suspected that someone in the history of humanity had probably already figured all this out years (or centuries) ago, so I researched to see how much of what I had found was already being taught. I found that very few of my focus areas were already documented or being taught. This is when I realized I had a calling to accomplish two big goals:

- Use these techniques to condition my entire body for flexibility.

- Teach these techniques to the rest of the human race, or as many people as I could get to listen. SequentialStretching.com is my first step toward this goal.

If I could devote several hours a day to sequential stretching, I thought that the first goal would probably take a couple of months to complete. I drastically underestimated that, as I am almost two and a half years into it and I still have a long ways to go to get my flexibility to the level where I want it. I eventually realized that this was going to be a multi-year or multi-decade process to reverse all the loss of flexibility that had accumulated over the first 40 years of my life.

For the first two years, I mainly focused on improving my own flexibility. I knew that teaching it to others was probably the more important goal, but I also had this suspicion that I would have trouble convincing others of the effectiveness of the techniques unless I showed how it had made drastic improvements in my own flexibility. In some ways, a fitness guru’s resume is written on the abilities of their own body. I didn’t think anyone would spend the time to learn a new technique that was entirely unproven. I knew it was helping me tremendously, but I had no easy way to show it. My body still had so much built-up tension to release, so I couldn’t yet demonstrate how it had helped me.

Starting to Teach

I tried giving a few short lessons to friends and family, but nobody had really gotten enthusiastic about it except myself. My flexibility was still significantly below average, as measured by the sit-and-reach box that I acquired around this time, so there was nobody to show the world how flexible they could become with these techniques. I decided to focus on the first goal so that I could at least use myself as an example of the effectiveness of the methods.

After a couple of years of focusing on the first goal, I remained convinced that it was improving my own flexibility and could be benefitting many others. I began to worry that I had made a great discovery for humanity, but I would be the only person who would benefit if I died before teaching others. My concerns about being able to prove my techniques remained, but if I could build enough content, I figured some people might try it anyway. Also, by the time I could begin to prove it by demonstrating how flexible I had become, I would already have training material ready for others to learn it. So, I decided to start working on both of the big goals at the same time.

SequentialStretching.com is my first effort to work on the second goal of teaching others what I have learned about improving flexibility. I hope it will be the first of many other methods of teaching these techniques, including instructional videos, in-person and virtual classes, as well as a book I intend to write.